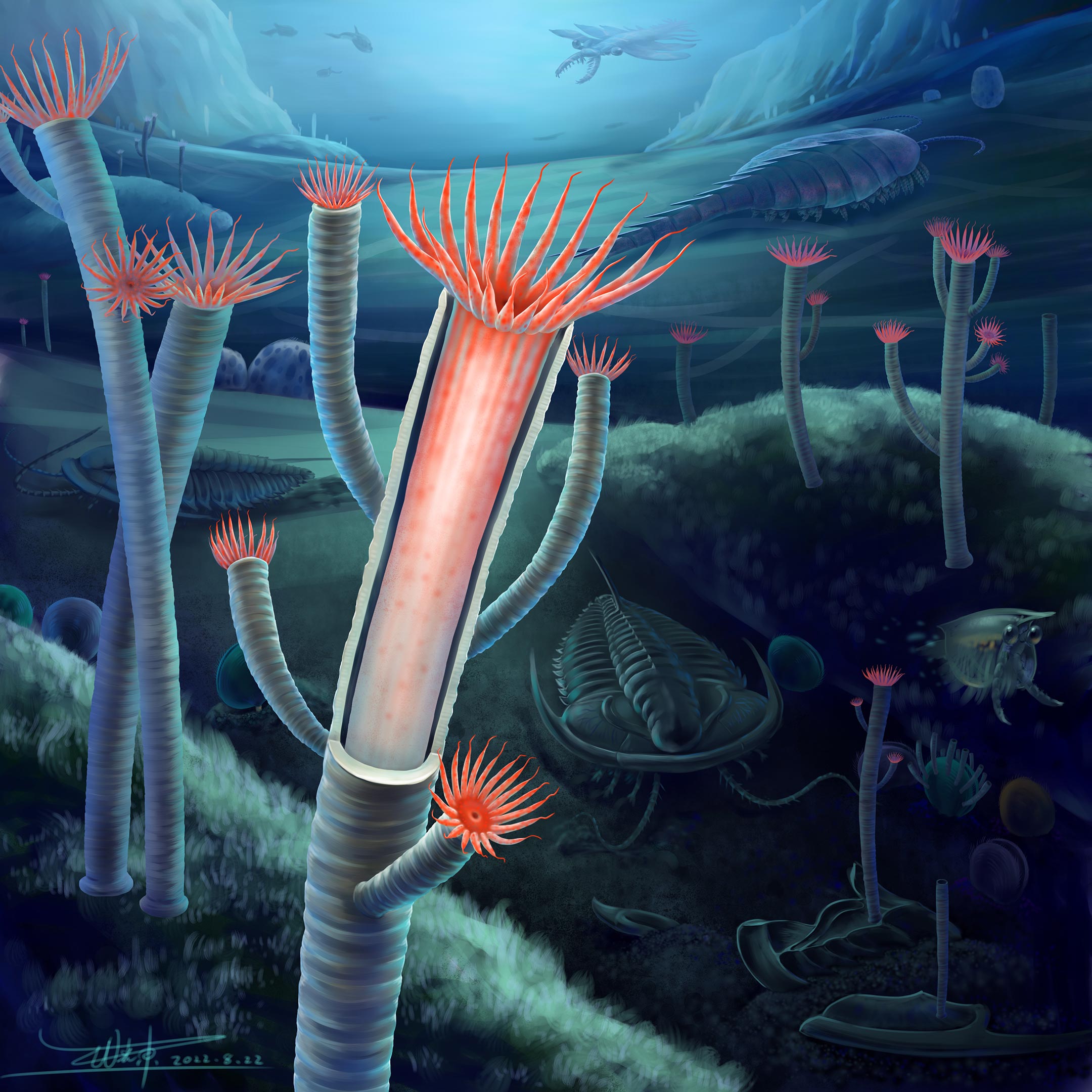

Umělcova rekonstrukce Gangtoucunia aspera, jak by se objevila v životě na dně kambrického moře asi před 514 miliony let. Část skeletu jedince v popředí je odstraněna, aby se ukázal měkký nádor uvnitř skeletu. Kredit: Rekonstrukce Xiaodong Wang

Vědcům se konečně podařilo vyřešit staletí starou záhadu evoluce života na Zemi a odhalit, jak vypadala první zvířata, která vyráběla kostry. Tento objev umožnila mimořádně dobře zachovaná sbírka fosilií, které byly objeveny ve východní provincii Yunnan v Číně. Výsledky výzkumu byly zveřejněny 2. listopadu ve vědeckém časopise Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Během události zvané kambrická exploze asi před 550-520 miliony let se ve fosilních záznamech náhle objevila první zvířata, která postavila pevné, silné kostry, a to mrknutím geologického oka. Mnohé z těchto raných fosilií jsou jednoduché duté trubice o délce od několika milimetrů do několika centimetrů. Typ zvířete, který vytvořil tyto kostry, byl však téměř zcela neznámý, protože postrádají zachování měkkých částí potřebných k tomu, aby je bylo možné identifikovat jako příslušníky velkých skupin zvířat, které jsou dodnes živé.

Fosilní vzorek (vlevo) a schematický diagram (vpravo) Gangtoconia aspera zachovalé měkké tkáně, včetně střeva a chapadel. Kredit: Luke Parry a Guangxu Zhang

Čtyři vzorky Gangtokonya aspera Se stále neporušenými měkkými tkáněmi, včetně střev a ústních částí, byl zařazen do nové skupiny 514 milionů let fosilií. Ty ukazují, že tento druh měl ústa obklopená prstencem hladkých, nerozvětvených drápů o délce asi 5 mm (0,2 palce). Je pravděpodobné, že byly použity k bodnutí a zachycení kořisti, jako jsou malí členovci. Ukazují to i vykopávky Gangtokunya Měl slepé střevo (otevřené pouze na jednom konci), rozdělené do vnitřních dutin, vyplňujících délku trubice.

Tyto rysy se dnes nacházejí pouze u moderních medúz, sasanek a jejich příbuzných (známých jako cnidarians), organismů, jejichž měkké části jsou ve fosilních záznamech extrémně vzácné. Studie ukázala, že tato jednoduchá zvířata byla mezi prvními, kteří vytvořili pevné kostry, které tvoří velkou část známého fosilního záznamu.

Podle výzkumníků Gangtokunya Vypadala by podobně jako moderní medúza scyphozoa s pevnou trubkovou strukturou připevněnou k základnímu substrátu. Ústa chapadla vyčnívala z trubice, ale mohla se zatáhnout dovnitř trubice, aby se vyhnula predátorům. Na rozdíl od polypů živých medúz, trubice Gangtokunya Vyrobeno z fosforečnanu vápenatého, tvrdého minerálu, který tvoří naše zuby a kosti. Použití těchto materiálů ke stavbě koster se postupem času mezi zvířaty stalo vzácnějším.

Detailní pohled na ústa gangu Tuconia aspera ukazující chapadla, která mohla být použita k ulovení kořisti. Kredit: Luke Parry a Guangxu Zhang

Dopisující autor Dr. Luke Barry, oddělení věd o Zemi,[{“ attribute=““>University of Oxford, said: “This really is a one-in-million discovery. These mysterious tubes are often found in groups of hundreds of individuals, but until now they have been regarded as ‘problematic’ fossils, because we had no way of classifying them. Thanks to these extraordinary new specimens, a key piece of the evolutionary puzzle has been put firmly in place.”

The new specimens clearly demonstrate that Gangtoucunia was not related to annelid worms (earthworms, polychaetes and their relatives) as had been previously suggested for similar fossils. It is now clear that Gangtoucunia’s body had a smooth exterior and a gut partitioned longitudinally, whereas annelids have segmented bodies with transverse partitioning of the body.

The fossil was found at a site in the Gaoloufang section in Kunming, eastern Yunnan Province, China. Here, anaerobic (oxygen-poor) conditions limit the presence of bacteria that normally degrade soft tissues in fossils.

Fossil specimen of Gangtoucunia aspera preserving soft tissues, including the gut and tentacles (left and middle). The drawing at the right illustrates the visible anatomical features in the fossil specimens. Credit: Luke Parry and Guangxu Zhang

PhD student Guangxu Zhang, who collected and discovered the specimens, said: “The first time I discovered the pink soft tissue on top of a Gangtoucunia tube, I was surprised and confused about what they were. In the following month, I found three more specimens with soft tissue preservation, which was very exciting and made me rethink the affinity of Gangtoucunia. The soft tissue of Gangtoucunia, particularly the tentacles, reveals that it is certainly not a priapulid-like worm as previous studies suggested, but more like a coral, and then I realised that it is a cnidarian.”

Although the fossil clearly shows that Gangtoucunia was a primitive jellyfish, this doesn’t rule out the possibility that other early tube-fossil species looked very different. From Cambrian rocks in Yunnan province, the research team has previously found well-preserved tube fossils that could be identified as priapulids (marine worms), lobopodians (worms with paired legs, closely related to arthropods today), and annelids.

Co-corresponding author Xiaoya Ma (Yunnan University and University of Exeter) said: “A tubicolous mode of life seems to have become increasingly common in the Cambrian, which might be an adaptive response to increasing predation pressure in the early Cambrian. This study demonstrates that exceptional soft-tissue preservation is crucial for us to understand these ancient animals.”

Reference: “Exceptional soft tissue preservation reveals a cnidarian affinity for a Cambrian phosphatic tubicolous enigma” by Guangxu Zhang, Luke A. Parry, Jakob Vinther and Xiaoya Ma, 2 November 2022, Proceedings of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences.

DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2022.1623

Přátelský webový obhájce. Odborník na popkulturu. Bacon ninja. Tvrdý twitterový učenec.